Reading Time: 12 minutes

Cities where people thrive with nature

From biodiversity to water and waste management, to keeping your favourite natural spot peaceful and secluded, cities are safeguarding the wellbeing of local people by protecting and enhancing their natural ecosystems.

During the Covid pandemic, one of the small rays of light that helped people to endure was the presence, and in some cases the return of nature to our cities. People found themselves exploring their local parks, revelling in the sounds of birds and following the life of the squirrels in their back gardens.

Cities have long understood that the natural world has positive effects on health and wellbeing, and natural ecosystems support processes like agriculture that make our urban lifestyles possible. Greener cities also make cooler cities, an important factor as climate change pushes urban temperatures up. That’s why cities are working hard to preserve and enrich green spaces within their territory, and why European policy that affects our natural world is of such importance to cities.

From policy to create greener and more biodiverse cities, to rules for keeping our water clean and minimising the waste that we pump into the earth, air and sea, cities and the European Commission have a tradition of boosting each other’s approach to a rich natural environment.

Many people living in apartment blocks didn’t have the opportunity to buy a house with a garden, but being in a city shouldn’t prevent you from experiencing nature.

– Erika Jacsmenik, Senior Expert of Debrecen’s Urban and Economic Development Centre, EDC Debrecen

From biodiversity to water and waste management, to keeping your favourite natural spot peaceful and secluded, cities are safeguarding the wellbeing of local people by protecting and enhancing their natural ecosystems.

During the Covid pandemic, one of the small rays of light that helped people to endure was the presence, and in some cases the return of nature to our cities. People found themselves exploring their local parks, revelling in the sounds of birds and following the life of the squirrels in their back gardens.

Cities have long understood that the natural world has positive effects on health and wellbeing, and natural ecosystems support processes like agriculture that make our urban lifestyles possible. Greener cities also make cooler cities, an important factor as climate change pushes urban temperatures up. That’s why cities are working hard to preserve and enrich green spaces within their territory, and why European policy that affects our natural world is of such importance to cities.

From policy to create greener and more biodiverse cities, to rules for keeping our water clean and minimising the waste that we pump into the earth, air and sea, cities and the European Commission have a tradition of boosting each other’s approach to a rich natural environment.

Momentum building for urban greening plans

Exciting developments are underway in cities across Europe, as they race to create and implement Urban Greening Plans. Part of the EU Biodiversity Strategy, these provide a framework for integrating nature into all local policies and financing. To gauge progress so far, Eurocities conducted a survey of 37 cities in 2021, revealing the biggest challenges they face. Among the top concerns were juggling competing interests for urban space, securing resources for long term maintenance, and coordinating across departments. As well as these difficulties, most cities emphasised the crucial need for strong political leadership and local expertise.

Specifically, 33 out of 37 cities, including major hubs Amsterdam and Paris, identified competing interests for urban space as a major challenge, while the same number, including Munich and Utrecht, highlighted the need for long-term maintenance of green infrastructure. The majority of cities also highlighted the importance of citizen engagement, public awareness, and public ownership, though to a slightly lesser extent.

The survey also found that cities around Europe have made great strides in restoring, protecting and enhancing their urban ecosystems and biodiversity over the past decade.

Turku has successfully shifted its maintenance philosophy to focus on enhancing biodiversity and urban ecosystems in both parks and city forests. Similarly, Utrecht has made significant progress by researching the bird and bat populations that share the city’s buildings and included mandatory nesting boxes in the procurement conditions of new developments.

However, cities face challenges in their policies, strategies, plans and actions. For example, while cities understand the importance of tree canopy cover, on average having about 28% of it across the wider urban area, many have highlighted challenges in increasing tree cover, from financing for long-term maintenance to selecting native and resilient trees. Cities have said that they need further funding and guidance in this, as in other areas of nature restoration. Lille Metropole pointed to challenges with managing spaces between urban areas, natural sites, and agricultural sites, while Madrid was among those that highlighted economic constraints.

To overcome these challenges, cities like Budapest and Dortmund have offered guidance, suggesting that Urban Greening Plans should aim to build trust and consensus among local people, and be backed by effective legislation. Other key principles, such as engaging with the private sector and academia, and considering the social and economic aspects of urban greening, were also mentioned as being crucial. By following these guiding principles, cities can take great strides in restoring, protecting, and enhancing urban ecosystems and biodiversity.

With nine green spaces recovered in all neighbourhoods, we want to guarantee a vegetable garden for every Florentine who wants it. A place to get close to nature, relax and cultivate! A sustainable dream that can come true.

– Dario Nardella, Mayor of Florence and President of Eurocities.

EU support for greening cities

The European Commission has taken several key steps towards supporting the greening of cities and protecting biodiversity since the approval of the European Green Deal in 2020. The Urban Greening Plans, discussed above, are one of the most significant developments. Another important proposal is the proposed Nature Restoration Law.

This legislation would help cities protect and restore green and blue urban spaces. It prioritises corridors that connect natural areas, and increase tree canopy cover. The law is intended to support the protection of urban biodiversity, which is essential for maintaining healthy ecosystems and improving the quality of life for city dwellers. However, many city administrations have noted the absence of biodiversity from targets specified in the law, and made the case that quality of green space is just as important as quantity.

Cities have also expressed concerns about targets proposed in the current version of the legislation, which takes a one-size-fits all approach. A target of 3% increases in urban green areas is much more onerous for cities that already contain lots of nature, and newer cities that do not have disused sites that can be repurposed. The shape of some cities can also mean that increased pressure for green areas would lead to urban sprawl, which could mean that older and more nature-rich spaces are built on instead of urban centres. Therefore, Eurocities has proposed replacing this target with a mandate for an increase that should be decided in agreement between local and national level.

Additionally, cities collect a lot of data on nature and biodiversity, and would like to see this data used in addition to the currently mandated EU satellite data, which sometimes contains errors and can lack the granularity available through local data collection.

The Urban Agenda Partnership on Greening Cities focuses on implementing the Nature Restoration Law, providing guidance to cities on how to work cross-departmentally and with external stakeholders, such as private landowners. The partnership also facilitates collaboration between national governments and cities on the regulatory and financing aspects of urban green infrastructure.

Espoo has identified the most valuable parts of the city for biodiversity and we are trying to save and enhance them.

– Tarja Söderman, Espoo Director of Environmental Affairs

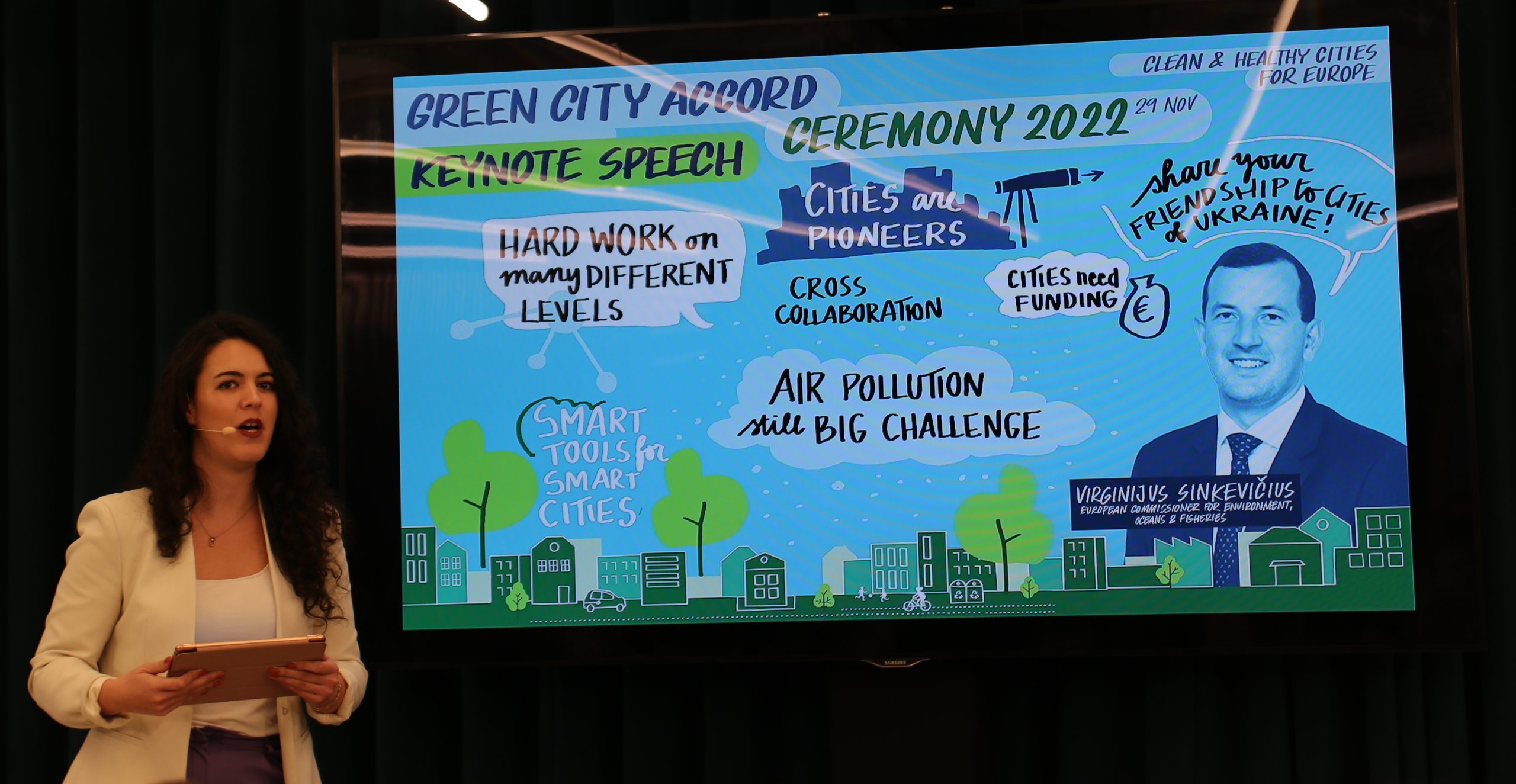

The Green City Accord

Paris is changing to be up to the challenges: pedestrianization, cycle paths, more nature and less space for the car.

– Anne Hidalgo, Mayor of Paris

Tackling waste

Cities also work to protect our environment by managing waste and waste water. Cities are largely responsible for setting up waste collection schemes, and three out of five wastewater operators are public companies owned by public authorities, mainly municipalities. Two new initiatives from the European Commission will have big effects in these fields. The Packaging and Packaging Waste Directive is being reformulated as a regulation, meaning that it will be in place more directly and uniformly across member states, and the Urban Wastewater Treatment Directive is also being revised.

Both of these are broadly positive for cities. The Packaging Regulation sets targets for reducing and recycling packaging waste, and requires certain levels of recyclability and recycled materials in new packaging. An important part of dealing with packaging waste is ‘extended producer responsibility,’ meaning that those who create the packaging must bear the costs of dealing with it in the waste stream. The framework for extended producer responsibility is set out in the Waste Framework Directive, and cities have expressed the importance of ensuring that the approach in this and the new regulation are harmonised.

Cities have demanded that extended producer responsibility must fully cover the costs of meeting packaging recycling targets, but also the costs of managing the packaging that remains in residual waste, the costs of cleaning up packaging-related litter and the operational costs falling to cities, such as door-to-door collection of waste.

Cities have also contributed smart ideas for making packaging recycling more efficient and effective. One such idea is using the QR codes that may be added to European requirements for labelling, for example to give people nutritional information, to also include information about disposal and recycling. Another is to ensure that information about compostable and biodegradable plastics reflects the reality on the ground, as many cities do not have the technology necessary to properly treat compost that contains these plastics to make it suitable for other uses, for example as fertiliser or animal feed.

Extended producer responsibility also comes up in the EU’s Urban Wastewater Treatment Directive, where cities will badly need the financing provided by polluters if they are to meet the new stringent rules for water treatment and the sustainability of treatment plants. The directive wants to see all wastewater treatment plants become energy neutral, for example by installing solar panels. Cities have welcomed this idea, while warning that depending on factors like their location, not all plants will be able to achieve this solely with onsite measures.

The total amount of investment needed to make all the changes mandated by this directive, along with the Drinking Water Directive, are enormous, standing at roughly €289 billion across the EU by 2030, according to the OECD.

Both new policies will be positive for cities and the world we all share, though honouring the ‘polluter pays’ principle, and ensuring that exemptions and loopholes don’t creep in are essential to effective implementation.

Cities are making significant progress in greening and protecting urban ecosystems and biodiversity, despite challenges in financing, coordination, and legislation. This is possible through building trust and consensus among local people, engaging with the private sector and academia, and considering the social and economic aspects of urban greening. The European Commission has taken important steps towards supporting this drive, including through the proposed Nature Restoration Law, and the revision of the Packaging Regulation and the Urban Wastewater Treatment Directive. By working together, cities, national governments and the European Commission can create a sustainable and healthy environment for their residents, wildlife, and the planet.

Embodied emissions in the built environment

Buildings are responsible for 40% of the EU’s energy consumption and 36% of its greenhouse gas emissions. The EU’s new Energy Performance of Buildings Directive seeks to address this. However, the carbon cost of a building isn’t limited to the energy it requires to operate. It’s also essential to consider the emissions associated with constructing the building and manufacturing the materials that it’s made of. According to cities and other experts consulted through Eurocities’ project ‘Dramatically Reducing Embodied Carbon in Europe’s Built Environment,’ the new directive must consider operational and embodied carbon, updating the definition of a Nearly Zero Energy Building to include embodied carbon metrics and setting a trajectory towards truly net-zero carbon buildings by 2050.

The end of a building’s life also needs to be considered. The Commission’s new Construction Products Regulation should promote circularity, minimum requirements for environmental impact and safety, and product certification to enable the recovery and reuse of construction products. Effectively reducing construction and demolition waste will also require mandatory pre-demolition audits, take-back schemes, extended producer responsibility schemes, capacity building, and knowledge-sharing networks.

When we are demolishing a building, we work with these companies to help inspire practices to reuse the waste material in construction.

– Anni Sinnemäki, Helsinki Deputy Mayor for Urban Environment

Growing noise pollution in cities

The 2021 Zero Pollution Action Plan aimed to reduce the number of people chronically disturbed by transport noise by 30% by 2030 relative to 2017, but Europe is on track for just a 19% reduction. A 2023 Eurocities survey on noise pollution with 14 respondents from cities around the EU found that several cities in Europe have conducted noise mapping exercises to measure their levels of noise pollution. Utrecht mapped every single street in the city and found that 55% of its population was exposed to noise levels above 55 dB, with the majority falling between 55-60 dB. Espoo mapped noise levels for main streets, regional and local collector streets, major roads, and railways in 2022.

The EU’s Environmental Noise Directive requires cities to protect ‘quiet areas’ but there isn’t a definition of what this is. Most of the local governments surveyed are taking action to develop ‘calm areas’ in their cities. Some cities have already identified and mapped existing quiet areas, while others are in the process of doing so. Many cities are choosing green spaces and squares as ideal locations for quiet areas, and some are using multi-criteria analysis to identify new potential spaces. Some cities are working on ongoing projects to improve existing soundscapes and create new types of quiet places.