Taking the pulse of European mayors

The Eurocities Pulse Survey is the flagship annual survey carried out across the broad membership of Eurocities, which brings together most of the major European cities, representing over 150 million people all over Europe. Drawing on 92 responses from leaders among Eurocities’ 210 member cities across Europe, this first edition aims to offer an overview of key urban trends, including the top challenges and priorities facing mayors one year ahead of the European elections.

What you will read here is the result of a selection of the main findings of the Pulse, with further analysis of the data to follow.

Contents

Contents

The Eurocities Pulse Survey is the flagship annual survey carried out across the broad membership of Eurocities, which brings together most of the major European cities, representing over 150 million people all over Europe. Drawing on 92 responses from leaders among Eurocities’ 210 member cities across Europe, this first edition aims to offer an overview of key urban trends, including the top challenges and priorities facing mayors one year ahead of the European elections.

What you will read here is the result of a selection of the main findings of the Pulse, with further analysis of the data to follow.

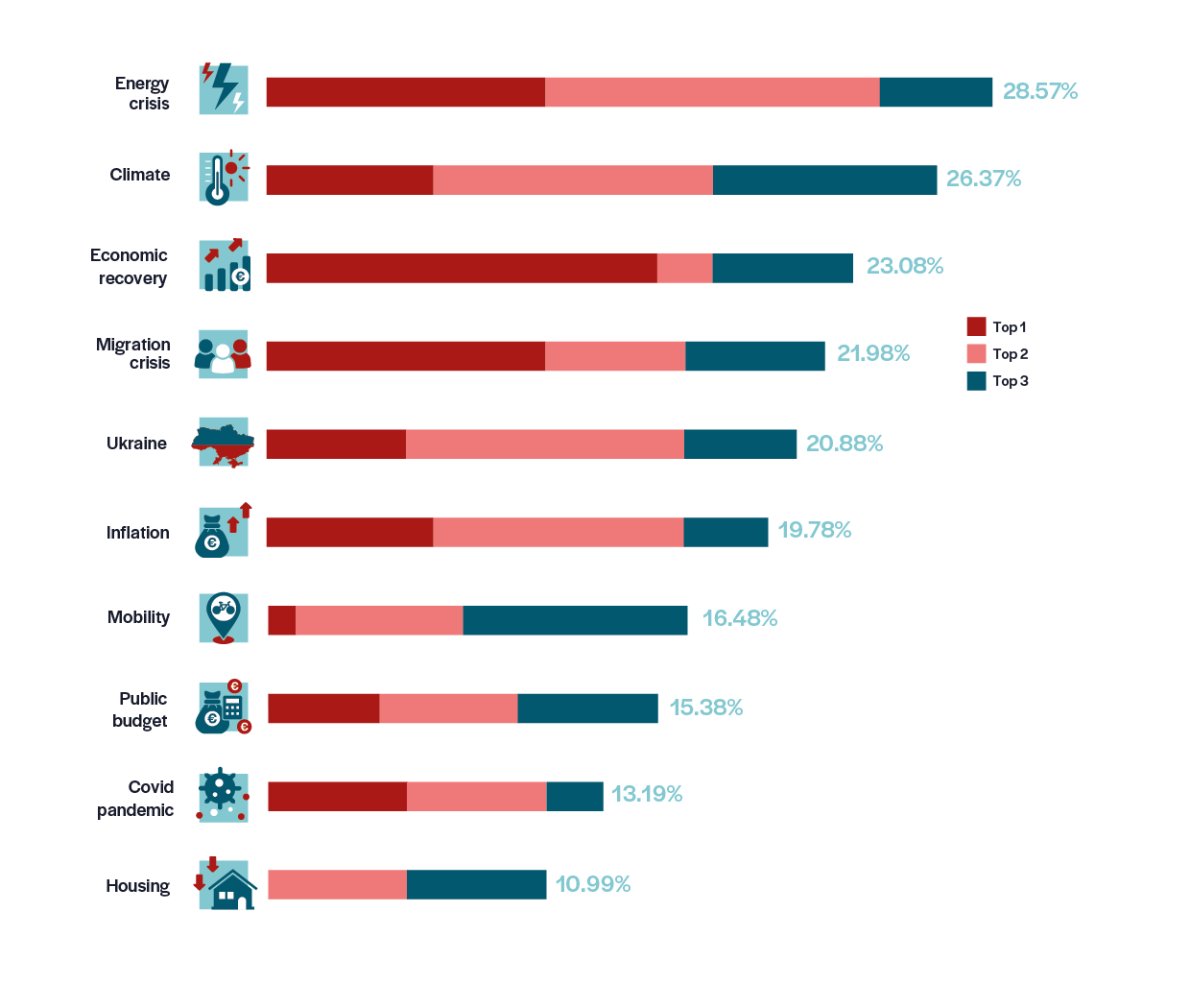

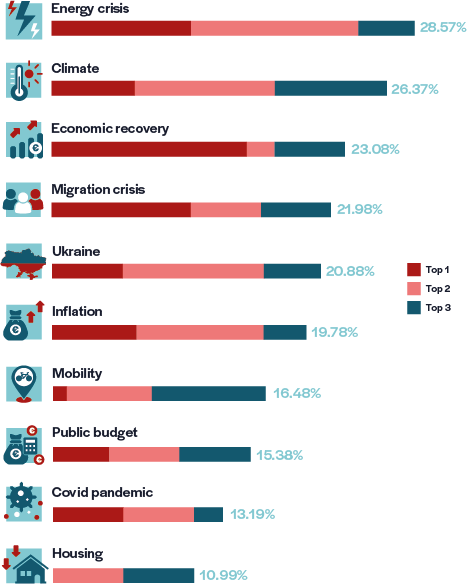

Top challenges in 2022 for European mayors

For European mayors from large cities, the top challenge in 2022 was the energy crisis, followed by climate change and the economic recovery. Overall, most of the top 10 challenges shared by European mayors reflect challenges that cropped up in the last three years and that have been faced by all levels of government across Europe, such as dealing with impacts of the Russian war in Ukraine, the effects of inflation or the ongoing recovery from Covid-19. Several other top challenges that mayors face reflect longer-term, ongoing challenges, that have crept up to the top of mayors’ agendas over successive years, such as the Europe-wide housing crisis, mobility and the constraints on local budgets. Whether the more recent or the long-standing challenges, all of them are covered by working groups and projects within Eurocities.

Mayors’ top 10 challenges in 2022

28.57% of European mayors mentioned the energy crisis among the top three challenges they faced in 2022, putting it as their overall top challenge. This chimes with a decision by Eurocities to make the energy crisis the top priority for 2023, covered across the network’s working structures, as well as a topic for this year’s focus section of the Eurocities Monitor. Rising energy prices have spurred mayors to speed up energy transition actions and promote local supply of renewable energies, as well as taking steps to protect the most vulnerable from energy poverty. The crisis has also led mayors to implement quick solutions to save energy and reduce costs, such as replacing street lighting with LED bulbs, or reducing the average temperatures public buildings are heated to. Similarly, while inflation registers as a lower challenge overall, mayors noted it for its effects on the most vulnerable sectors of society, who have already been hard hit by the pandemic, and for its squeezing effect on public budgets, with implications for public service delivery. Mayors highlight that next to measures to minimise the impact of the cost of living crisis on the most vulnerable households, they also had to quickly develop schemes to support local businesses. The impact of inflation in cities is discussed in more detail further down.

Climate change, referred to by many mayors as the climate crisis, was mentioned by 26.37% of all mayors as a top three challenge in 2022. It has been rising to the top of political agendas for years and is one of the key areas of expertise, developed through projects and policy focus, of Eurocities. 2022 was a year of extreme weather: droughts, heat waves, floods and heavy snowfall. Mayors shared the challenges of dealing with a new normal. For mayors, this can mean finding ways to adapt to new realities – Athens has a Chief Heat Officer, while Paris and Gothenburg are adapting local infrastructure and amenities to deal with excess rain – and ways to mitigate the worst effects of climate change in order to keep up with their ambitious climate neutrality objectives. For example, many are implementing local energy communities, or Climate City Contracts to reduce overall energy demands. At the same time, mayors noted that preparing and implementing their ambitious climate neutrality plans last year was not easy, and they were particularly concerned about the best ways to bring local people on board.

The economic recovery is the third highest-rated challenge by mayors, with 23.08% noting it as one of their top three challenges. However, with 15.38% of mayors choosing this in the no.1 position, it is by far the top challenge when looked at this way. The Covid-19 pandemic and lockdowns had a huge effect on the economic and social development of our cities, with many retail businesses, food services, hotel industries and tourism-linked businesses going bankrupt, and local social services often being overwhelmed by new needs and requests. Some mayors noted the challenge of accessing recovery funding schemes, both EU and national, attracting private investments and targeting this support towards often complicated projects to speed up the green and digital transformations.

For mayors, managing the economic recovery can also mean making sense of new scenarios, such as finding ways to encourage people back to public transport, which suffered a drop in passenger numbers, or putting more resources into speeding up the digital transition, offering more e-government services to reflect changing habits, or building better public spaces, bringing more green to the city. Overall, mayors highlight their sense of responsibility to avoid economic stagnation and to use the crisis as an opportunity to build back better.

At the same time, and to a lesser extent, some mayors still found themselves having to implement pandemic measures such as physical distancing in 2022, which is why Covid-19 is noted as a separate challenge to the recovery (position nine, at 13.19%).

Migration ranks fourth in the top challenges reported by mayors, but is connected very closely to number five, Russia’s war in Ukraine, given that the current migration flows are particularly linked to the huge numbers of Ukrainian refugees as a consequence of this Russian war in Europe. With around seven million Ukrainians leaving their country in a very short space of time, the natural destination for most was big European cities, with cities in Eastern Europe bearing the greatest responsibility for integrating and providing services to new populations. For example, Warsaw, which became host to around 300,000 refugees the first three months of the war, also swelled by 15% overall. The war is further considered by mayors to be the cause of other challenges they face, such as the growth in the overall cost of living. Moreover, for some Eastern European mayors in particular, one challenge was dealing with social tensions with Russian speaking minorities and the removal of Soviet era monuments. Under the leadership of Dario Nardella, President of Eurocities, the network was particularly active in supporting Ukraine, both in the short term via knowledge exchange on how to welcome refugees, and in the long term via the preparation of a sustainable reconstruction of Ukrainian cities. This is explored in greater detail in the special section on Ukraine.

The state of public finances, in terms of local budgets, was considered a top challenge by one in six mayors. Beyond inflation, the Covid-19 pandemic required unprecedented public spending to support businesses and local people during turbulent times, while it also resulted in lower tax revenues. In a similar vein, the green and digital transition need huge investments. While the European Union has offered important investments, in particular via the National Recovery and Resilience Plan and its RepowerEU initiative, it wasn’t guaranteed that cities were involved in the distribution of these funds, and several national governments made it difficult for larger cities to access them.

It is unsurprising to see housing in the top 10 challenges reflected by mayors, as the housing crisis has been evident for many years in urban areas. There is urgent need not only to provide far more affordable housing units in our cities, but to also keep in mind environmental targets. The topic continues to be an important strand of Eurocities activities.

Over the longer term, it will be interesting to see which topical challenges stay high on mayors’ agendas, with the energy crisis and impacts of inflation both threatening to yield longer-lasting pain. This is why we will repeat the Eurocities Pulse Mayors Survey on an annual basis and include it in each edition of the Eurocities Monitor.

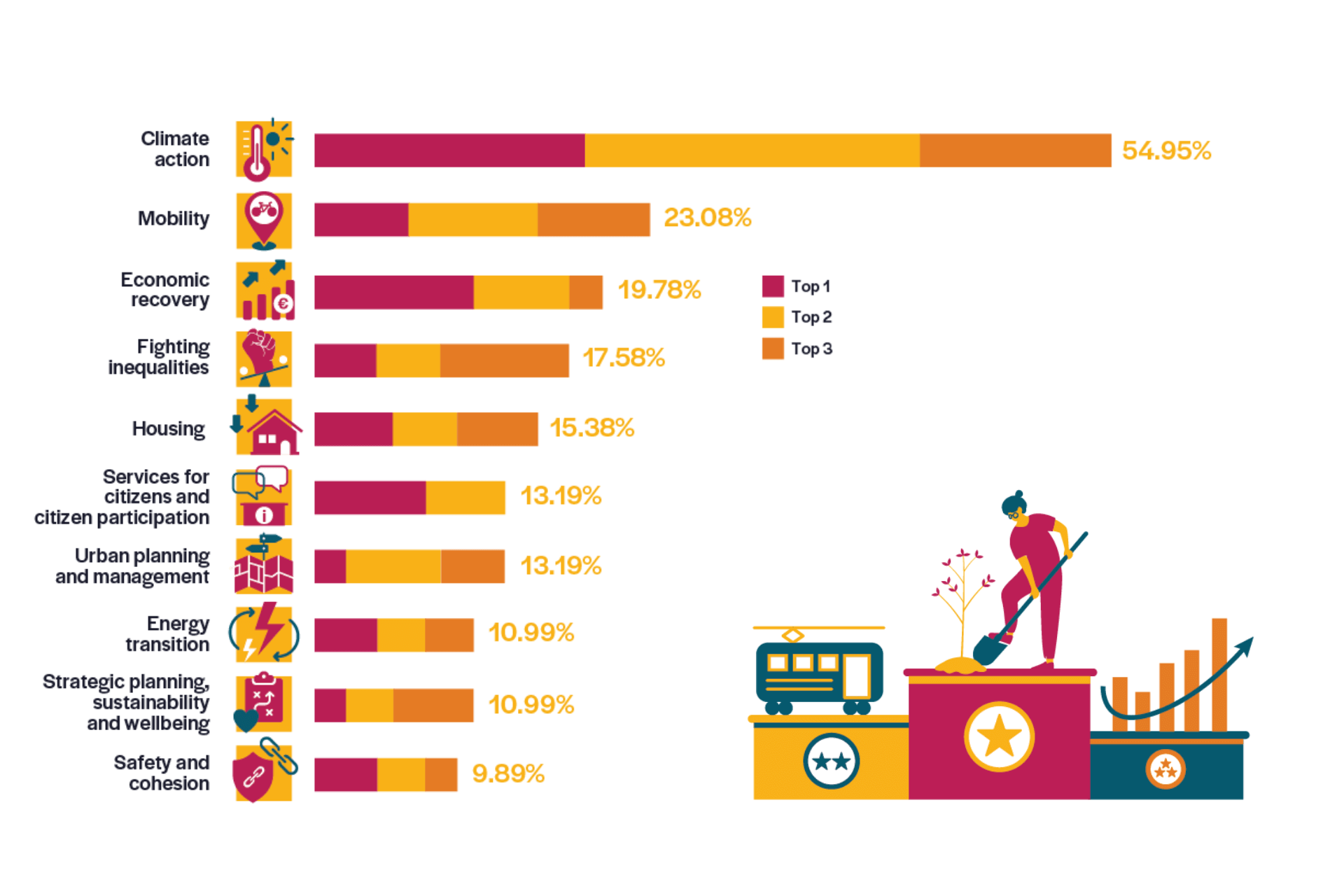

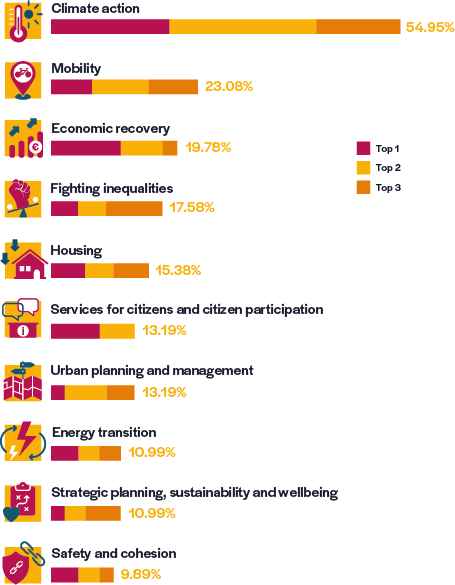

Top priorities for mayors for 2023

Climate action is by far the top priority for 2023, with more than half of mayors selecting it – more than double any other category. Given that many mayors have committed their city to climate neutrality targets, climate action at local level is more than a response to climate needs, but about inspiring and implementing a whole-of-society approach, by bringing local people, businesses and others on board in a combined effort. In their reflections, mayors mention concrete measures, such as developing low emission zones; steps to protect the environment, such as adding more greenery in the city or tackling air pollution; and promoting the circular economy and more sustainable practices throughout the city and in the city services. Climate action is strongly linked with mobility, which is the second highest priority, and the energy transition, another of the top 10 priorities for mayors.

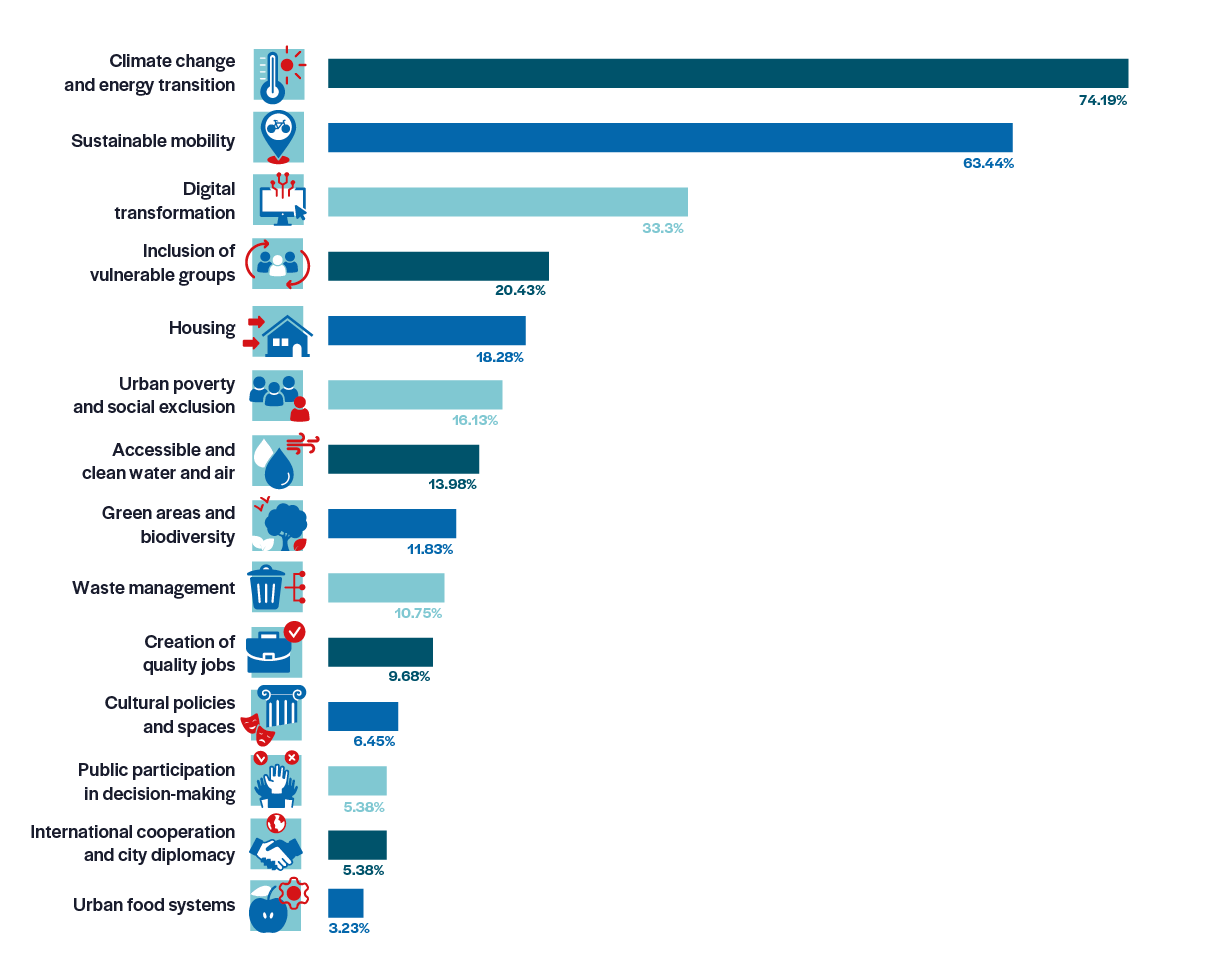

Top priorities for mayors for 2023

Climate action is by far the top priority for 2023, with more than half of mayors selecting it – more than double any other category. Given that many mayors have committed their city to climate neutrality targets, climate action at local level is more than a response to climate needs, but about inspiring and implementing a whole-of-society approach, by bringing local people, businesses and others on board in a combined effort. In their reflections, mayors mention concrete measures, such as developing low emission zones; steps to protect the environment, such as adding more greenery in the city or tackling air pollution; and promoting the circular economy and more sustainable practices throughout the city and in the city services. Climate action is strongly linked with mobility, which is the second highest priority, and the energy transition, another of the top 10 priorities for mayors.

Mayors’ top 10 priorities in 2023

The focus on sustainable mobility scores comparatively much higher among mayors’ priorities than it did as a challenge, and it is closely linked to the first goal to reduce carbon emissions. Many mayors will continue implementing the infrastructure projects that in some cases were already set up and financed in 2022, under the post-Covid recovery funding. There is a recurrent focus on developing and expanding metro and tram lines, renewing green bus fleets, developing pedestrian and bicycle infrastructure, and improving traffic management.

One out of five mayors put implementing the economic recovery as a top priority. Specifically, for many mayors this means implementing the ambitious and transformative recovery plans that were set up to respond to the pandemic. This entails finding ways to manage large investment portfolios that need to be implemented quickly across often complex projects that promote more sustainability, resilience and inclusive economic growth. For example, Riga plans to create a new metro line, and better connections between the railway and urban transport system, made accessible through a single ticketing system.

There is a clear difference between the themes of the challenges mayors face and the priorities they are engaged with. For example, mayors’ reflections on priorities are much more tied to improving urban liveability, such as by fighting growing inequalities, which was the fourth-highest priority, and focussing on services for citizens and citizen participation than on the structural demands of the job. For example, many mayors mentioned plans to involve more, and more diverse, voices in decision making processes, by setting up more citizens’ dialogues, or finding ways to gather inputs from young people. In their comments on climate, many mention the need for a just transition, and when talking about sustainable urban mobility, many mayors highlighted how they will promote it as part of the culture of the city, and as a key enabler for a better quality of life.

With more people at risk of poverty as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic and inflation, mayors point to growing social divides in their cities. Consequently, mayors are implementing targeted measures to help the most in need. This includes dedicated support and new social services to tackle new forms of poverty (such as energy poverty), and more targeted support to children, youth, the elderly and migrants.

Linked to inequalities, many mayors also prioritise housing (fifth-highest priority) with a focus on increasing the housing stock for more affordable and social housing, as well as supporting local people’s access to decent housing with a minimum standard of living.

Improving urban planning and urban management is a priority that is often linked to the top two, i.e. climate action and mobility, but covers many other actions ranging from greening the city and making it more walkable, to developing plans to reactivate or reimagine how to use different areas of the urban space. Many mayors highlighted their concern to make such changes in consort with their local populations, and therefore plan to use evaluation systems to monitor public uses and satisfaction. Mayors are eager to leverage the power of good planning to improve the quality of life in the city.

The mayors also highlight how they aim to prioritise and implement new frameworks for strategic planning, sustainability and wellbeing. This can mean launching long-term and holistic strategies and action plans – linked for example to the implementation of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals or city net zero plans – and that link to the economic, environmental and social dimensions of sustainability. Additionally, some mayors talk about integrating concepts such as the 15-minute city into their operations.

Rounding out the top 10 mayors’ priorities for 2023 is safety and cohesion, which translates into promoting a sense of security in the city as well as promoting tolerance.

Cities in the eye of the storm

How can we make sense of the context in which Europe’s city leaders operate?

We could borrow an analogy from geology of different strata of government, laid down across time. Most European cities date back to medieval times, often the days of Ancient Greece and Rome. And many European city governments can trace their origins to freedoms won or charters granted in the 12th or 13th centuries, when cities were very much the most important force in the lives of their citizens. But the 16th to the 19th century development of nation states introduced a very powerful layer. Many big innovations in government – from professional armies, to national banks and currencies, or new national services including post, rail and road networks – were creations of the nation state, as were the wars that ravished Europe’s cities in the first half of the 20th century. More recently, Europe’s nation states have been overlaid by international organisations of the post-war period.

Geological metaphors, however, are not sufficiently dynamic to describe reality on the ground. Europe’s city leaders are more like sailors, with currents, tides and wind interacting in unpredictable ways. Despite the advent of powerful national and international governments, cities have continued to supply vital services and develop new ones for their citizens. In the 19th and early 20th century, Europe’s cities often led the way in pioneering social and infrastructural services (public transport, sanitation, policing and lighting) later adopted by nation states. Today, European cities retain their own municipal institutions, civic cultures and political ambitions.

Urban, national and international governments sometimes align, sometimes oppose. National governments provide most public funding, but with this comes dependency and restraint, often resented by urban leaders. Despite its directly elected parliament, the EU is meant to answer first and foremost to its member states. For most of its existence, the great part of its budget went to rural areas.

More recently, however, the EU has developed an active regional and cities agenda, funding economic development, social inclusion and climate. Still more recently, the EU and cities have started making common cause against the populism and democratic backsliding of some national governments. All the while, governments at all scales find themselves subject to atmospheric pressures of technological disruption, globalisation and shifting geo-politics.

The job of leading Europe’s cities is exciting and highly challenging, being so close to people and places that tend to be rich in history, culture, community and public life, often liberal and forward-looking in spirit and increasingly well connected with other city governments, thanks to networks like Eurocities.

European cities are not as evidently dominant in the world’s economy or politics as in the age of European empires, but they have retained and perhaps augmented their soft power. Many are experimenting with radical new approaches to development, inclusion and climate action. Some commentators argue that 19th century Europe is a model for the 21st: dense, mixed activity and car-free – albeit with electric bikes and scooters substituting for horses and carts. Forward to the past!

The challenges come from the severely limited funding and powers at cities’ disposal. Despite all the policy talk from institutions like the EU, OECD and UN about empowering cities, Europe’s urban governments have gained few new powers, and in some countries, particularly those with populist regimes, have actually lost them. At the same time, European city leaders face growing pressures: rising inequalities, climate change and ecological breakdown, pandemics, disruptive technologies, war and mass migration, populism and nativism. If we are entering the age of the permacrisis, cities are in the eye of the storm.

The Eurocities Pulse survey gives us a fascinating snapshot of the current concerns of urban Europe as seen by its leaders. The first thing worth underscoring is how fast-moving political developments are. Over one generation, cities in Eastern Europe have gone from building post-Soviet political and economic systems to grappling with energy prices, carbon emissions, refugee integration, inflation and housing– all exacerbated by the war in Ukraine. In Western Europe, preoccupations with post-war reconstruction, and de-industrialisation have had to make room for ecological and social imperatives.

Second, urban priorities have a distinctive character. How many national leaders would rank mobility, citizen participation and new frameworks of wellbeing – or even housing – among their top priorities? Yet these loom large in the Eurocities Pulse survey. City voters have distinctive concerns stemming, in part perhaps, from their backgrounds (often younger, more highly educated, and recent migrants) and in part from the pressures of crowded city life.

Third, city leaders are struggling to address the strategic challenges, in the press of urgent, short-term ones. According to the Eurocities Pulse survey, while most mayors’ current priorities fall into the ‘immediate and urgent’ category, they are looking forward to turning to the ‘long-term and important’ ones next year!

All this points to the essential role of organisations devoted to supporting European city governments. Eurocities has grown over the last few decades into a leading network, connecting city leaders, encouraging peer learning and collaboration and amplifying local administrations’ voice on national, continental, and international platforms. The European Cities Programme at LSE Cities, funded by Bloomberg Philanthropies, was only set up in 2021. But we have become increasingly convinced of the potential for an academic centre devoted to researching European cities and building the capacity of city governments and the skills of current and future European city leaders.

By Ben Rogers

Bloomberg Distinguished Fellow in Government Innovation and Director of the European Cities Programme at LSE Cities

Working with the EU to promote local priorities

When asked how they expect the EU to support them with these priorities going forwards, the European mayors responded on the need for a more direct dialogue between cities and the EU, and on the need to simplify and make more direct all sources of EU funding for cities.

When it comes to establishing a direct dialogue between cities and the EU, there are many existing structures, narratives and examples to draw on that shape local policy today and that are strongly supported by Eurocities. The Urban Agenda for the EU, via its partnerships between city authorities, national ministries and the European Commission, is unique in bringing together all these collaborators to work on specific aspects of urban affairs. Some highlight how this way of working should be strengthened with more political ownership and structural support. The implementation last year of the 100 Climate Neutral and Smart Cities Mission offers a broad approach towards climate neutrality by taking into account how cities work in practice.

Mayors highlight that the EU could support their economic recovery efforts by simplifying procedures for the absorption of EU funds and making sure that EU funds can flexibly be adapted to ongoing and future crises such as with the refugees, energy, and economic shocks. They further point out that EU funding schemes could help them more if they would provide direct support or, more generally, if they would be deployed by taking the local needs into account and by empowering them in their implementation.

In relation to the priority of climate action, mayors point to the need to reduce paperwork and bureaucracy for EU funds, while also developing more targeted legislation that can empower them and help them in delivering realistic targets aligned with local needs. Mayors highlight that financial tools for cross-border projects and international collaboration would help them develop and scale-up impactful climate solutions.

When it comes to implementing their priorities, mayors commented that EU regulation and policies can play both a positive role to accelerate change, or a negative one by ignoring local priorities. For example, in relation to their housing priority, mayors highlight that current EU rules do not allow them to implement the necessary changes and they would view positively an EU regulation that regulates real estate, promotes public housing and restrains housing price increases in cities.

Non-EU mayors point to the need for new policies and funding options for local administrations of candidate countries, which could be administered through city-specific approaches or by supporting cross-border actions between cities, both within and outside of the EU.

How do Mayors expect the EU to support them with their priorities?

European mayors working with the EU level

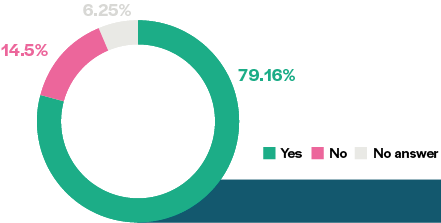

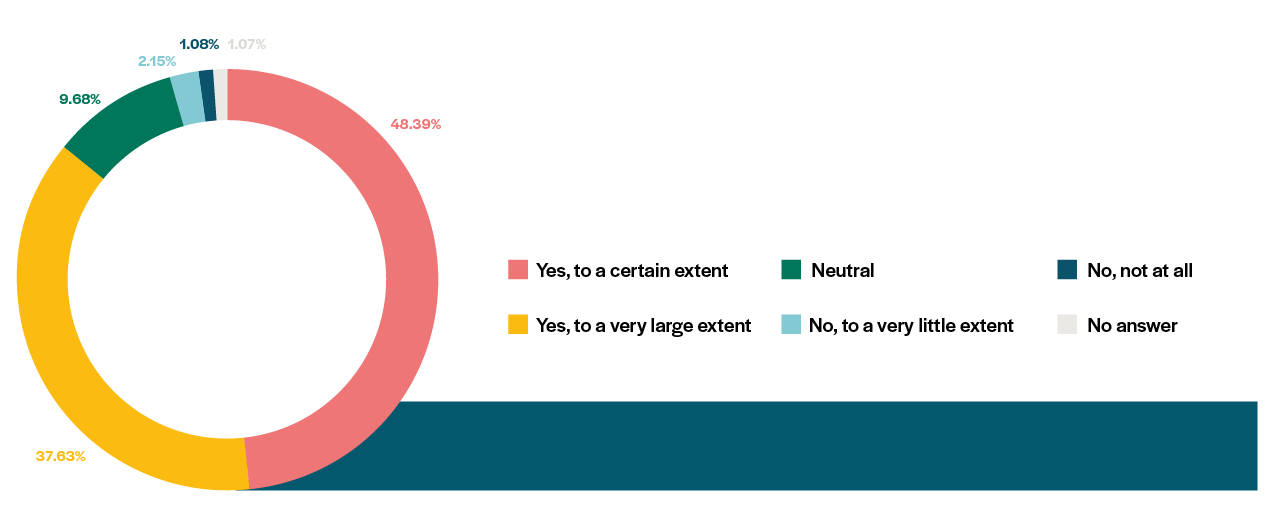

As a mayor from a European city, do you feel that you are contributing to EU policy priorities and processes?

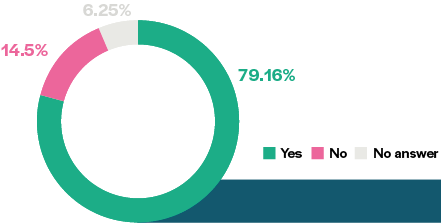

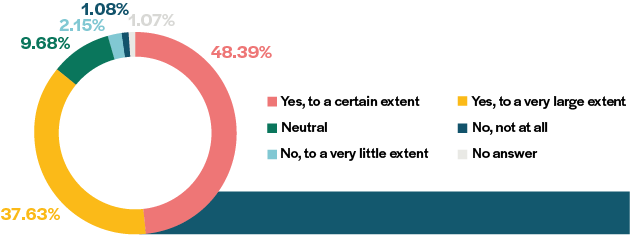

European mayors have a very clear understanding that their action is dependent on the EU and that the EU is dependent on them. To mayors, the idea that one can tackle the most difficult problems of today without cooperation across levels of government is something that belongs to the past. This is very clear and undoubtedly part of the reason why almost 80% of our sample of 92 mayors (which rises to 92% when non-EU mayors are excluded), feel that they are contributing to EU policy priorities and processes.

The mayors are very aware of their active role in implementing a vast array of EU policy, such as via the European Pillar of Social Rights, or territorial investments earmarked through the EU’s Cohesion Policy (amounting to around €20 billion to be directly managed in the current EU budget) or EU recovery plan; and in their active participation through other fora, such as the 100 Climate Neutral and Smart Cities by 2030 Mission, as well as more generally on helping to deliver the goals of the European Green Deal. Mayors further reiterate their key role for EU institutions to coordinate and tackle multiple crises. Mayors were at the forefront of the Covid-19 and refugee crises, where the constant interaction between mayors and the EU level demarcates two clear examples of this growing relationship.

In their examples, mayors also highlight how they are not just implementing EU priorities on the ground, but many are increasingly personally involved in the EU political and legislative processes to ensure that the EU rules and funds support the real needs of city dwellers.

Additionally, they see an important role for themselves in raising awareness to the general public about the EU and EU agendas, and in feeding back to the EU on how policy works in practice – much of which is boosted through collaboration in networks like Eurocities. Another feature that many mayors were keen to talk about was the further role of city networks like Eurocities to foster policy-learning through exchanges of best practices and other means.

The few mayors that do not feel they are contributing to EU policies are mostly from candidate-countries or the UK. Among the EU mayors who feel they are not contributing to EU priorities, most explain that this is not due to lack of interest from their side but rather due to their feeling that, despite their efforts, they are not really setting the EU agenda as they wished, with their inputs provided via official consultations too often being overlooked, which links to the next point.

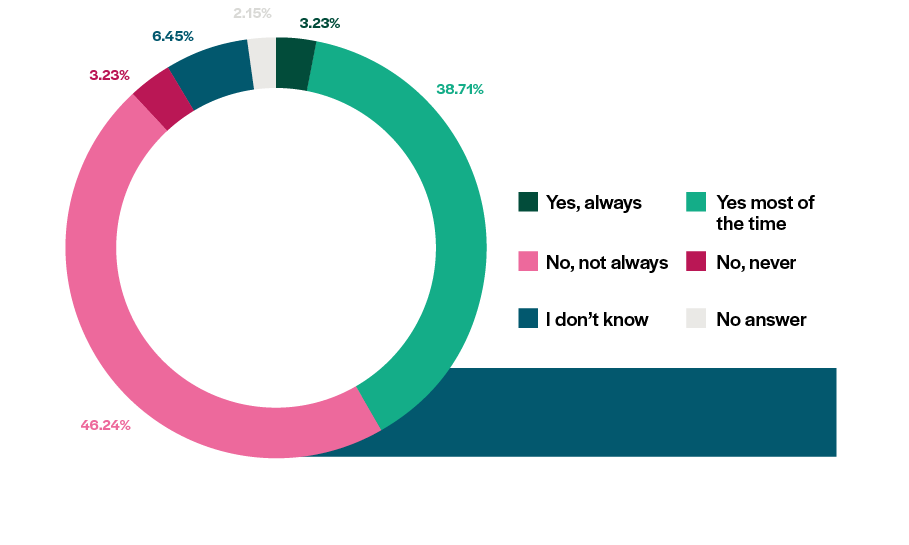

Almost 50% of mayors feel that the EU institutions and policies tend not to take into account their specific needs and the potential that cities offer. When limited to only EU based mayors, this number is somewhat more positive – with 50% answering “No, not always”, and 40.7% saying “Yes, most of the time”. This means that 52.6% of mayors from cities within the EU consider that the EU institutions and policies do not or not sufficiently take into account the specific needs and potential of cities. There is thus a huge potential for the EU institutions to work better with cities, a potential that Eurocities wants to develop with concrete proposals for the upcoming European elections.

A big factor in some of the negative sentiment shared by mayors was linked to expectations for a greater role for cities, rather than EU member states, in managing and using the post-Covid-19 recovery funding under the EU’s Recovery and Resilience Facility, as well as in the current Cohesion Policy programmes. The experience shared by many cities throughout the pandemic was one of being at the forefront of a crisis in which urban centres were hardest hit, and which has implications for future urban planning. Against this background, mayors lament a worrying centralisation trend in EU funds, a sentiment felt particularly strongly among Eastern European mayors who highlight how EU funds are being used by national governments as a political weapon against opposition mayors.

Do you feel that the EU institutions and policies take into account the specific needs and potential of cities effectively?

Another factor often cited concerns a perceived lack of a strong connection between city needs and EU action, with mayors saying that they do not consider they have adequate, direct, contact with the European Commission. Rather, there exists a fragmented landscape of many EU initiatives, and no horizontal coordination over urban matters at EU level, such as could be better managed via a European Commissioner for Urban Affairs. Given the growing role of cities in achieving EU objectives, mayors see the need for a preferential mechanism for engaging cities and their elected representatives in EU decision-making, both regarding the preparation and the implementation of EU policies and legislation.

Many mayors cited that there is not enough support to develop green infrastructure and promote a just transition locally, nor enough attention given to the needs of cities when it comes to the renovation wave or climate mitigation policies. For example, the current EU proposal for a new Nature Restoration Law does not take into account the starting points of different cities, especially those with plentiful green spaces.

The same is often true regarding the misalignment of EU funding priorities and the real needs of cities, which are changing rapidly in response to many of the challenges already listed above. In relation to this, some mayors point to the lack of human resources available within their city administrations. This means that they do not have the necessary person-power to use the full potential of financing instruments available for cities. They therefore call for more focus on capacity building and administrative capacity.

On the other hand, roughly 42% of mayors do think their needs are taken into account, which rises to almost 45% when limited to mayors of cities in the EU. When asked to give a positive example, highlights included the earmarked budget for urban investments under the EU’s Cohesion Policy, which opens up new possibilities for urban transformation; and a greater flexibility to combine different EU funds to focus on integrated urban development and promote metropolitan thinking. For example, in Italy, the PON METRO, the national operational programme for metropolitan cities, directly made available funds for over €800 million to Italy’s 14 major metropolitan cities, which was later supplemented by €1.2 billion through REACT-EU, an exceptional additional programme launched by the European Commission to help respond to and recover from the pandemic. In the next programming period the regular allocation will rise to €3 billion and will be extended to mid-size cities in Southern Italy.

Additionally, the existence of several programmes with dedicated financing, such as via the European Social Fund Plus, is highly appreciated as it helps to tackle specific urban needs around poverty, immigration and other areas. Moreover, as mentioned above, the creation of many new tools and frameworks, as well as the 100 Climate Neutral and Smart Cities Mission, helps to put new attention on cities as the main drivers localising the European Green Deal, and Europe’s transformation.

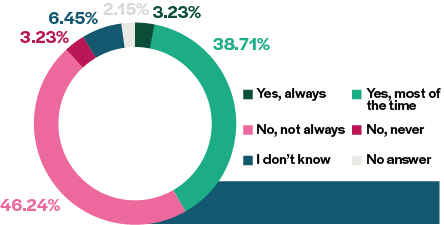

Around 45% of the mayors surveyed suggest that they have encountered situations where current EU rules and policies prevent them from achieving their goals – this rises to more than 50% when only EU mayors are considered. Given the growing importance of the EU for cities and vice versa, this is not surprising, but does highlight some areas for improvement. For example, mayors report on EU rules for social housing often being too strict for a city to invest effectively; the EU rules on state aid not allowing them to support their municipal companies, SMEs and start-ups as they would like; and the EU budget rules undermining the ability of cities to choose their public spending strategies and promote public investments.

Another gripe commonly shared among mayors concerns EU public procurement rules, which are focused on promoting the EU’s single market and competitiveness and negate the possibility for local authorities to include environmental and social criteria in their contract conditions that would ensure, among others, living wages and fair work conditions. Furthermore, EU data rules are not effectively supporting cities in their efforts to manage the impact of short-term holiday rentals, and, more generally, data management in the public interest.

When it comes to EU climate legislation, mayors appreciate the ambition at EU level, but as in the case of the Nature Restoration Law already mentioned above, they highlight the importance of working with cities to take into account specific local conditions and avoid one-size-fits-all solutions.

Have you encountered situations where current EU rules and policies prevent you from achieving your goals at the local level?

Mayors’ financial needs in key policy areas

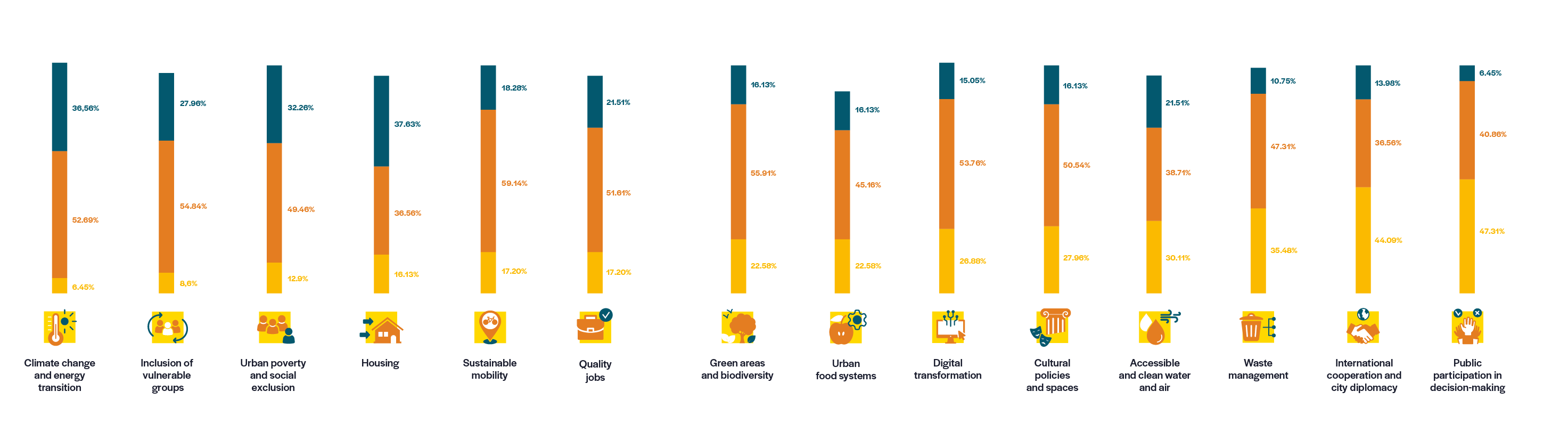

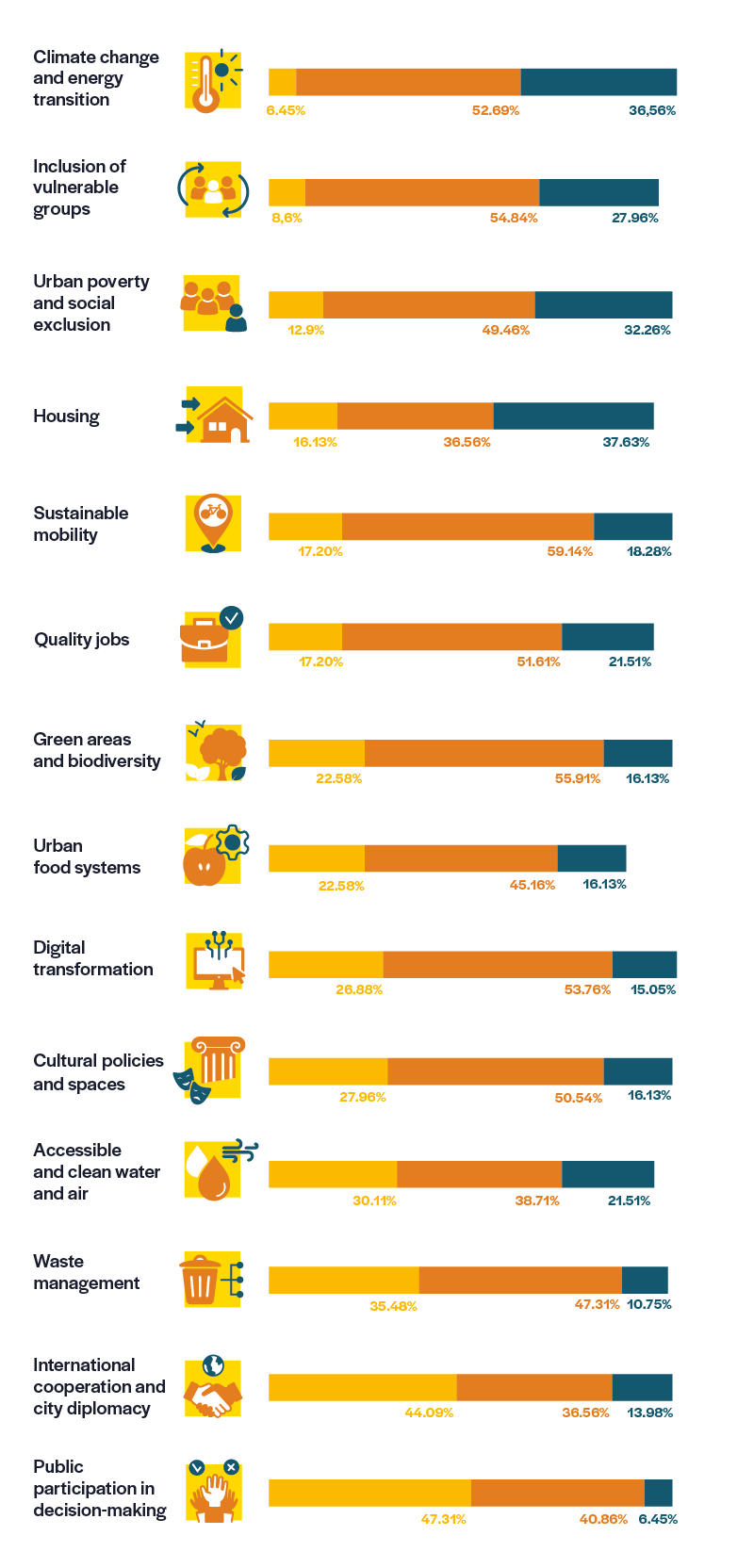

When it comes to their expectations of being able to fund different priorities and where the greatest gaps exist in their projections for the next five years, mayors clearly highlight that current resources are not enough. This is particularly true for climate action and the energy transition, two top priorities, for which only 6.45% expect to have enough resources to meet needs. For the majority of the top priorities for 2023, including migration, urban poverty, housing, and sustainable mobility less than one out of five mayors expect to have enough resources.

As a Mayor of an EU city, do you feel that you are contributing to EU policy priorities and processes?

While it’s clear that most mayors report they will not be able to fully fund urban needs in each of these areas, the majority (50-80%) do believe they will have enough resources to sufficiently match these needs. Still, this means that for priorities like housing, climate and the energy transition, there are still 37.63% and 36.56% of mayors respectively who do not expect to have enough resources, with 32.26% also saying they will not be able to sufficiently cover challenges around urban poverty and social exclusion.

The fact that financial gaps at city level exist in these fields is not new, but given the unprecedented resources made available around Europe for the post-Covid recovery, some of those numbers could still appear to be unexpected. This would point to the fact that those recovery investments do not always reach cities and that they are not always aligned with cities’ needs.

On the other hand, for some mayoral priorities, such as public participation in decision making, waste management, and city diplomacy the situation is more positive, with respectively only 6.45%, 10.75% and 13.98% of mayors not expecting to have enough resources.

Regarding sustainable mobility, which registered as mayors’ second top priority, only 18.28% do not expect to have enough resources, as opposed to 17.2% who do. One other area where it is anticipated for many more resources to be needed in the coming years is the digital transformation, in which many cities are already well ahead of the game, but where only 26.88% of mayors expect to have sufficient resources.

Mayors’ expectations from EU funding

As highlighted by mayors responding to the Eurocities Pulse Survey 2023, EU funding is an essential support for cities. In the coming five years, an unprecedented amount of EU funds will be invested in cities, and in some cases these funds will be implemented directly by cities. These funds are naturally deployed to support EU priorities and objectives, especially investment into the twin transformations. For example, the EU Recovery plan has earmarked a minimum of 37% spending on climate and biodiversity and 20% to digital measures, while for the current EU budget period, 2021-27, EU Cohesion Funds earmark a minimum of 30% for climate action and put a strong emphasis on investments in sustainable mobility and infrastructure.

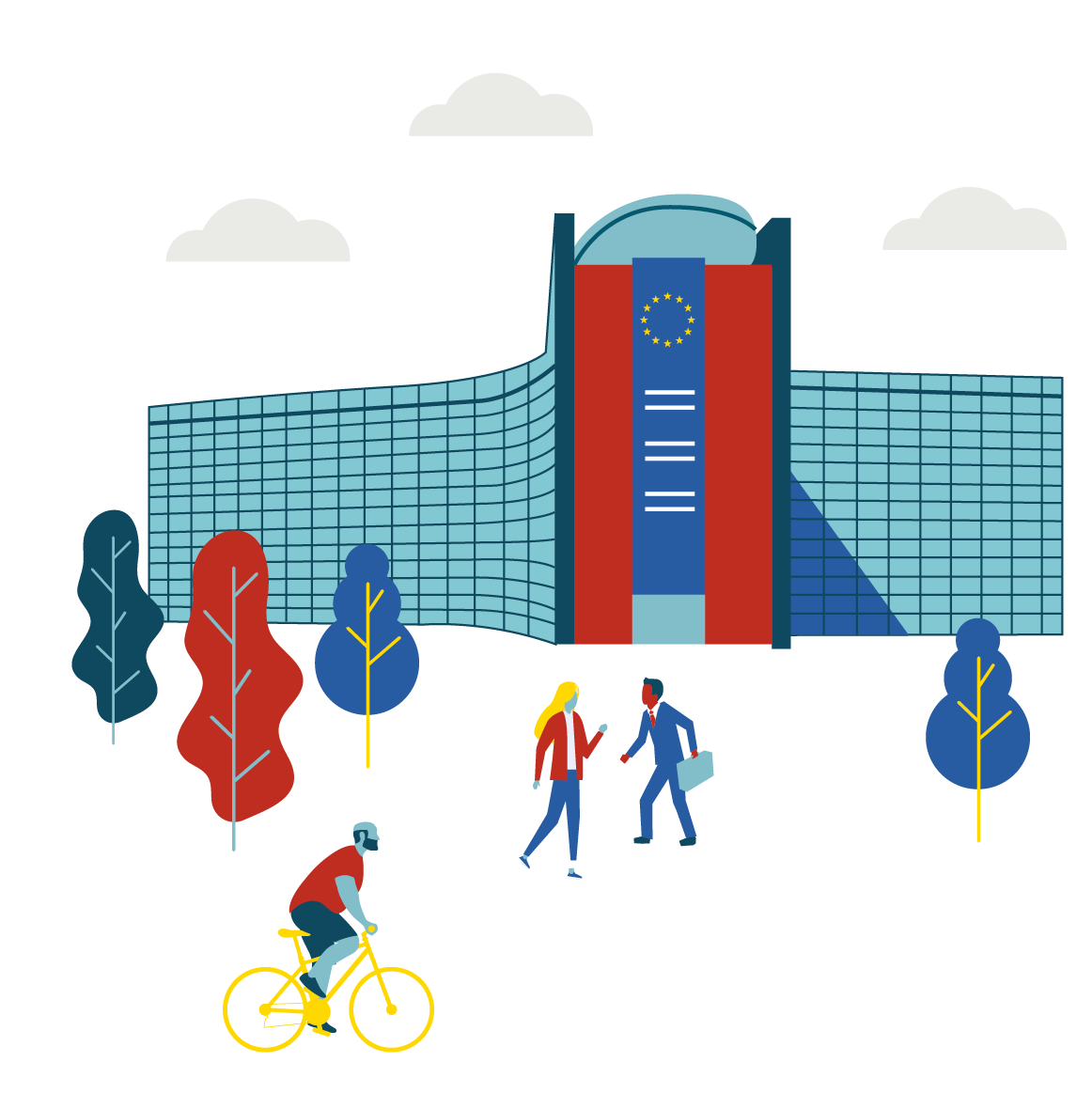

With this in mind, it is not surprising that mayors expect climate change and energy transition (74.19%), sustainable mobility (63.44%), and digital transformation (33.33%) to be the top three areas where EU funding will make the biggest difference to their policy objectives in the next five years. At the same time, given that climate and mobility are the two top priorities overall for mayors in 2023 (graph 2), this shows that mayors anticipate working with the EU to meet these goals.

According to you, which are the three main areas where EU funding makes the biggest difference to your policy objectives in the next five years?

Looking at these results in relation to mayors’ financial needs for their priorities, it is clear that EU funding is helping mayors to somewhat cover the huge financial gaps for climate and energy investments, while more investment is still needed. Meanwhile, it is also clear that such alignment is not perceived by mayors for other priorities where resources will be insufficient to match needs, such as housing and the inclusion of refugees, migrants, ethnic minorities and people with disabilities. EU funding therefore does not seem to be a major force contributing to closing the financial gap in these areas, at least when compared to the other top areas highlighted above.

Impact of inflation on cities

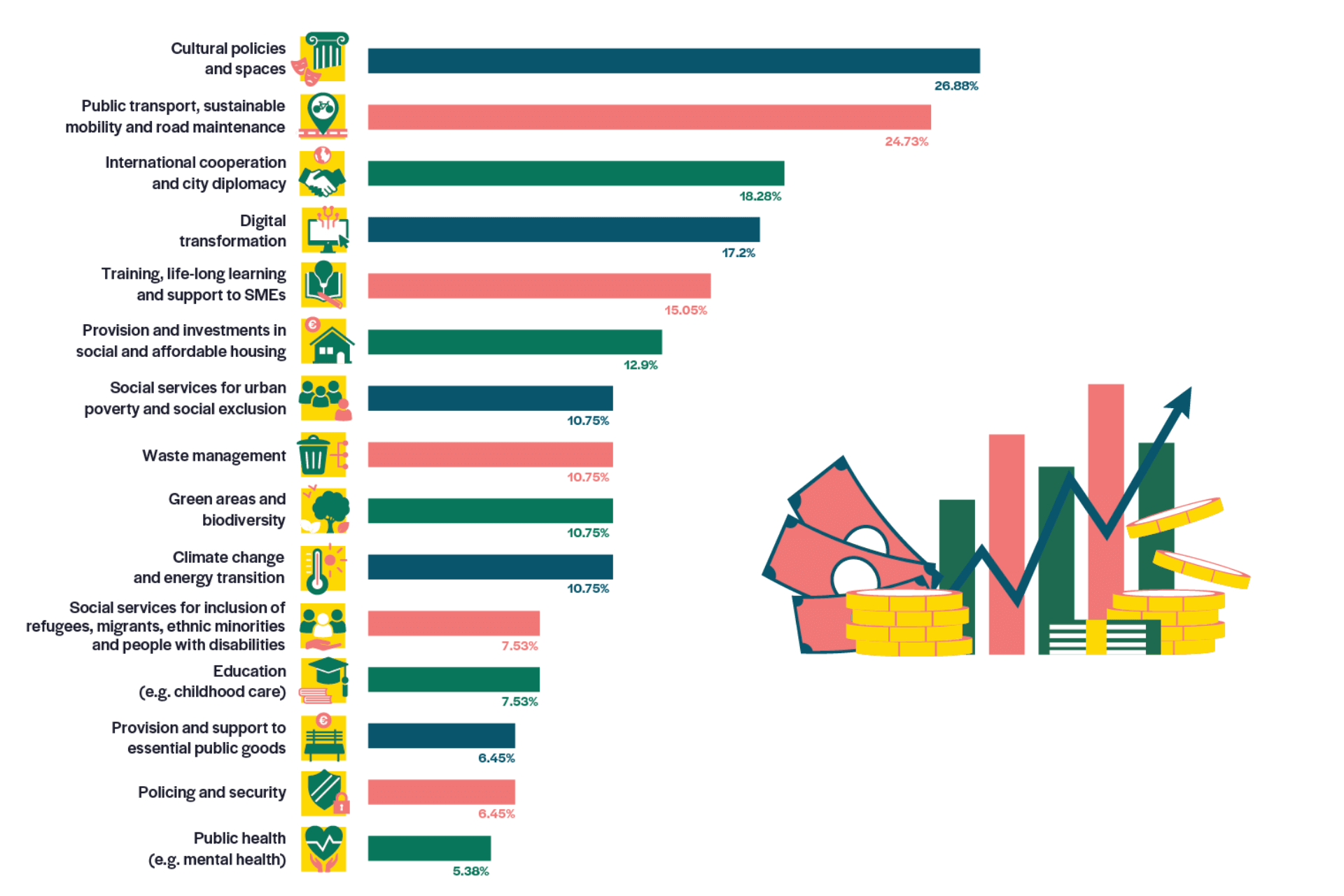

Part of these calculations on financing needs is made on the basis of high inflation across Europe, with the jump in prices impacting cities’ supply lines as well as public consumption patterns. At city level, over 86% of mayors said the current high-level of inflation had affected their ability to make strategic long-term investments. And although the areas targeted by the resulting budgetary cuts were quite diverse, over 25% cut their budgets for cultural policies and spaces, including sports facilities, with almost one quarter making similar cuts in investments into their budgets for public and sustainable transport and road maintenance.

During the pandemic years, these have perhaps been two of the most obvious areas to cut, given that many cultural institutions were closed during the lockdowns, and because passenger numbers on public transport dropped as people stayed away from city centres. However, now such considerations must be made in a different context.

Mayors are trying so far as possible to avoid cuts to important public services, but as they have no choice in the current setup, they are often forced to reduce support or investments – which doesn’t necessarily mean cutting services and activities – in areas that are more sensitive to inflation, such as cultural spaces and sports facilities, public transport, sustainable mobility and road maintenance, international cooperation and city diplomacy.

It is difficult to foresee how inflation will evolve in the coming years, but if the current high levels of inflation remain in the medium to long term, a constant reduction of investments in these areas might have implications for the quality of services.

At the same time, the data suggests that mayors are particularly wary of reducing municipal support or postponing planned investments in areas that are crucial for the functioning of the city, such as public health, policing and security, as well as the provision and support to essential public goods (e.g. water).

During the pandemic years, these have perhaps been two of the most obvious areas to cut, given that many cultural institutions were closed during the lockdowns, and because passenger numbers on public transport dropped as people stayed away from city centres. However, now such considerations must be made in a different context.

Mayors are trying so far as possible to avoid cuts to important public services, but as they have no choice in the current setup, they are often forced to reduce support or investments – which doesn’t necessarily mean cutting services and activities – in areas that are more sensitive to inflation, such as cultural spaces and sports facilities, public transport, sustainable mobility and road maintenance, international cooperation and city diplomacy.

Is the current high level of inflation affecting mayors’ ability to make strategic long -term investments?

It is difficult to foresee how inflation will evolve in the coming years, but if the current high levels of inflation remain in the medium to long term, a constant reduction of investments in these areas might have implications for the quality of services.

At the same time, the data suggests that mayors are particularly wary of reducing municipal support or postponing planned investments in areas that are crucial for the functioning of the city, such as public health, policing and security, as well as the provision and support to essential public goods (e.g. water).

Given the current inflation and energy crises, have you already, or do you plan to reduce either your city’s support or postpone planned investment in the following public services?

Mayors engaging in city diplomacy

Mayors are increasingly engaged in matters concerning international affairs, both in their direct interactions with other levels of government, and in their outreach to and coordination with other cities, including through city networks like Eurocities. Mayors understand that if they want to stand a chance to solve local challenges they need to win the support of and cooperate with all levels of governments, including supranational ones. At the same time, supranational institutions and actors are very much aware of how important it is to directly engage cities to deliver on cross-border and global challenges, as highlighted in the guest essay by LSE Cities.

At city level, this represents a growing ability to project urban needs, and have this better reflected in policy and initiatives of all kinds. Given the continued urbanisation of European populations, understanding this power dynamic, and better profiling the voice of mayors, will lead to better policy that is more able to reflect real needs of people on the ground by offering practical solutions that ultimately work towards global and international goals.

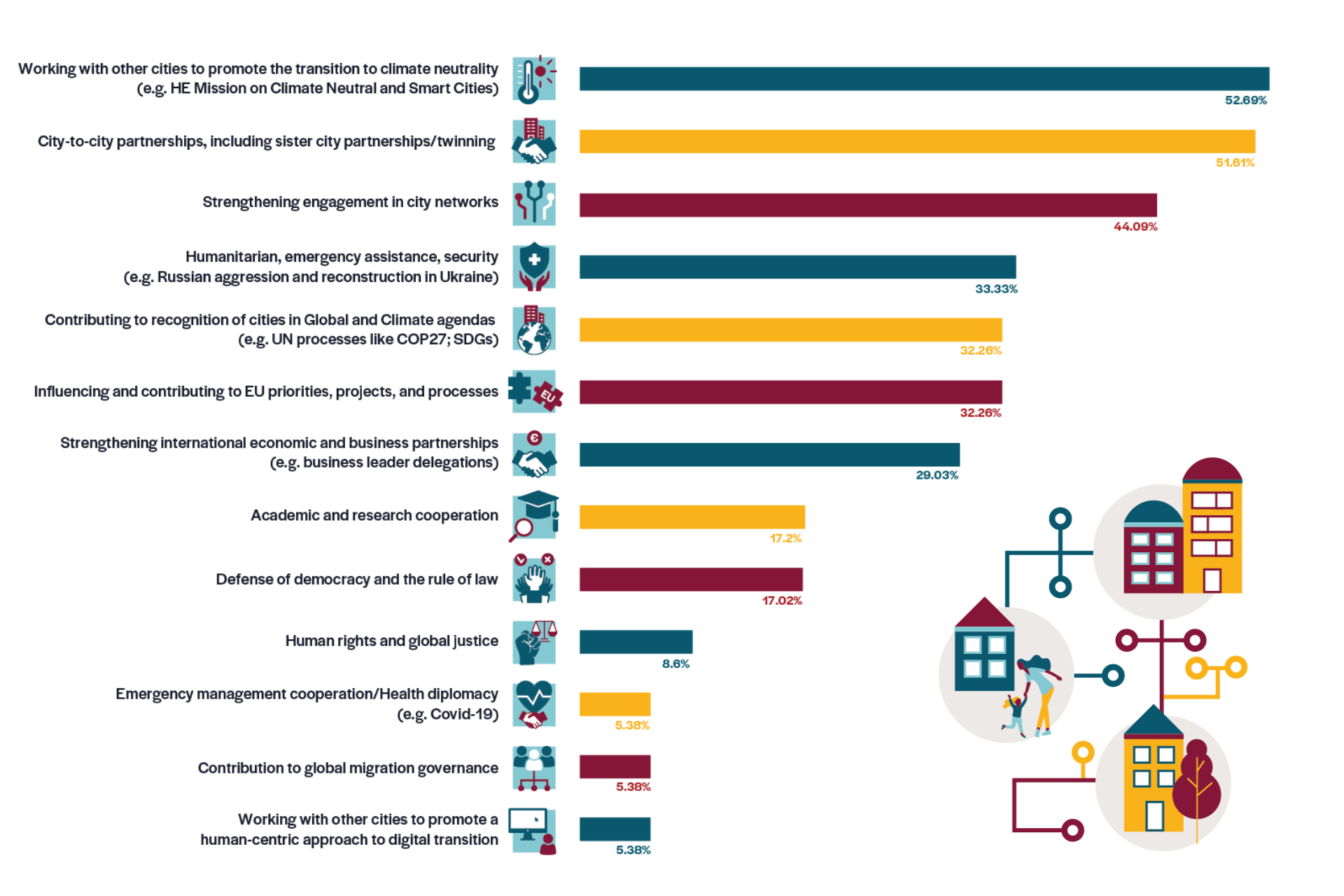

Mayors’ top ambition (52.69%) in the area of city diplomacy closely matches their top priority of climate action, given that a majority would like to focus on working with other cities to promote the transition to climate neutrality. This work is already happening, for example through the Mission, but it is important to expand and upscale all work in this area, to share lessons as widely as possible, as cities lead the way towards a climate neutral Europe. This can also help strengthen the basis for the recognition of cities in global and climate agendas.

Which are the top three areas for you to engage in city diplomacy activities?

Another two areas of high importance are strengthening engagement in city networks (44.09%) and engaging in city-to-city partnerships (51.61%). For cities, these relationships can be crucial multipliers for positive effects, and are especially important for cities’ ability to project their growing power in other domains, such as working with sister cities in Ukraine, or finding ways to offer humanitarian and emergency assistance, as many Eurocities member cities have been able to do for their sister cities in Turkey in recent months.

One third of mayors listed humanitarian, emergency assistance, and security, in their top areas for city diplomacy, with many mayors expecting to further engage in activities to support Ukraine’s resistance and reconstruction. When it comes to climate action, mayors are not only eager to work with each other to scale up solutions, but they also have an ambition to shape global sustainability and climate agendas. One third of mayors put their engagement in UN activities such as COP27 or the implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals as a top priority. Unsurprisingly, a similar amount also view influencing and contributing to EU priorities, projects, and processes as a top priority.